Aging of Population

Leonid A. Gavrilov

and Patrick Heuveline

This is a manuscript of our

article in The Encyclopedia of Population.

[Note: This original

manuscript is slightly different from the final publication because of

small

editorial changes.]

Reference

to the published article:

Gavrilov L.A., Heuveline

P.

“Aging of

Population.”

In:

Paul Demeny and Geoffrey McNicoll (Eds.)

The Encyclopedia of Population.

Aging

of population

(also known as demographic aging, and population aging)

is a

summary term for shifts in the age distribution (i.e., age

structure) of

a population toward older ages. A direct consequence of the

ongoing

global fertility transition (decline) and of mortality

decline at

older ages, population aging is expected to be among the most prominent

global

demographic trends of the 21st century. Population aging is

progressing rapidly in many industrialized countries, but those

developing

countries whose fertility declines began relatively early also are

experiencing

rapid increases in their proportion of elderly people. This pattern is

expected

to continue over the next few decades, eventually affecting the entire

world. Population aging has many important socio-economic and

health

consequences, including the increase in the old-age dependency ratio.

It presents challenges for public health (concerns over possible

bankruptcy of

Medicare and related programs) as well as for economic development

(shrinking

and aging of labor force, possible bankruptcy of social security

systems).

Defining and measuring population

aging

As the study of population aging is

often driven by a concern over its burdening of retirement systems, the

aging

of population is often measured by increases in the percentage of

elderly

people of retirement ages. The definition of retirement ages may vary

but a

typical cutoff is 65 years, and nowadays a society is considered

relatively old

when the fraction of the population aged 65 and over exceeds 8-10%. By

this

standard, the percentage of elderly people in the

A related measure of

population aging is the elderly dependency ratio (EDR): the

number of

individuals of retirement ages compared to the number of those of

working ages.

For convenience, working ages may be assumed to start at age 15,

although

increasing proportions of individuals pursue their education beyond

that age

and remain, meanwhile, financially dependent, either on the state or,

increasingly, on their parents or bank managers. The ratio of the

elderly

dependent population to the economically active (working) population is

also

known as old-age dependency ratio, age-dependency ratio

or elderly

dependency burden and is used to assess intergenerational

transfers,

taxation policies, and saving behavior.

These indicators of

population aging are mere head-count ratios (HCR), that is,

they simply

relate the number of individuals in large age categories. These

indicators fail

to take into account the age distribution within these large

categories, in

particular among the elderly. When the fertility and mortality trends

responsible for population aging have been fairly regular over time,

the

population growth is positively correlated with age (i.e., the oldest

age

groups are growing fastest). This implies that if the proportion of the

population over age 65 is increasing, within that 65-and-over

population the

proportion over, say, age 80 is also increasing. As health, financial

situation, and consumption patterns may vary greatly

between

65 year-olds and 80 year-olds, simple ratios conceal important

heterogeneity in the elderly population. Increasingly, attention is

paid to the

"oldest olds" (typically age 80 and over). A long-time subject of

curiosity,

the number of centenarians is growing even faster. Estimated at 180,000

worldwide in 2000, it could reach 1 million by 2030 (United Nations

2001).

The

second class of indicators for population aging is the group of

statistical measures

of location (median, mean and modal ages of population). The median

age

-- the age at which exactly half the population is older and another

half is

younger -- is perhaps the most widely used indicator. For the year

2000, the

median age in the

Since population aging

refers to changes in the entire age distribution, any single indicator

might

appear insufficient to measure it. The age distribution of population

is often

very irregular, reflecting the scars of the past events (wars,

depression

etc.), and it cannot be described just by one number without

significant loss

of information. Were the age distribution to change in a very irregular

fashion

over the age range, for instance, much information would be lost by a

single-index summary. Therefore, perhaps the most adequate approach to

study

population aging is to explore the age distribution through a set of

percentiles, or graphically by analyzing the population pyramids.

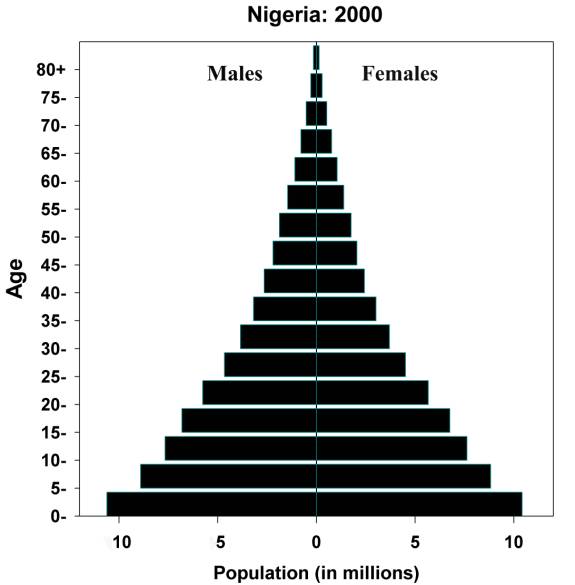

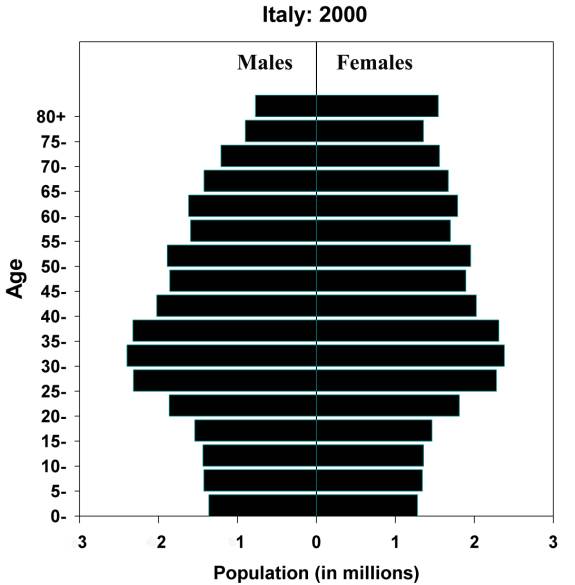

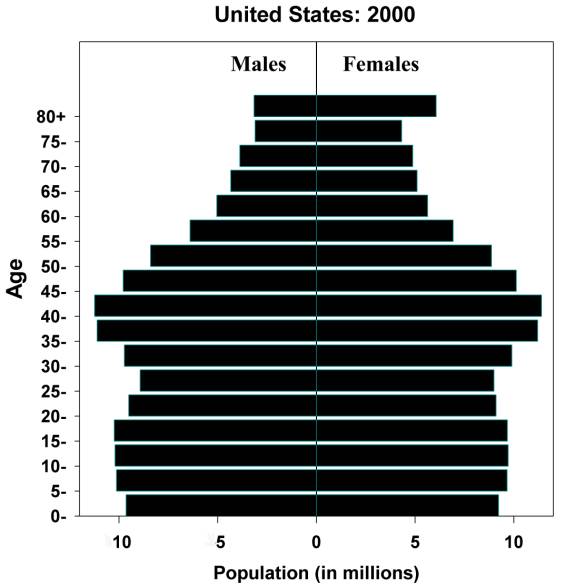

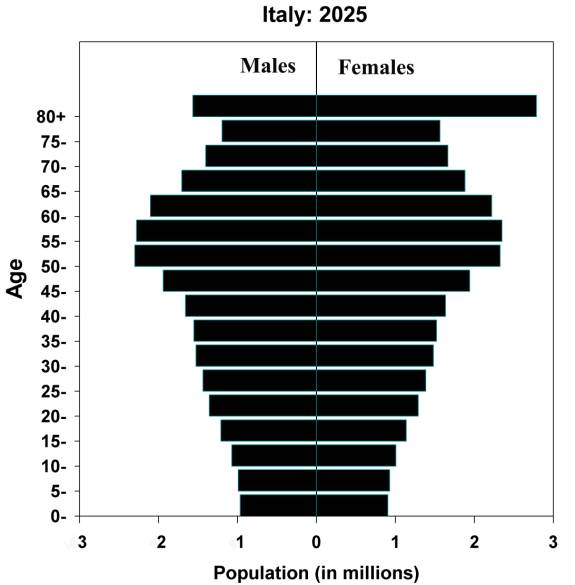

Demographers commonly use population pyramids to describe both age and

sex

distributions of populations. Youthful populations are represented by

pyramids

with a broad base of young children and a narrow apex of older people,

while

older populations are characterized by more uniform numbers of people

in the

age categories.

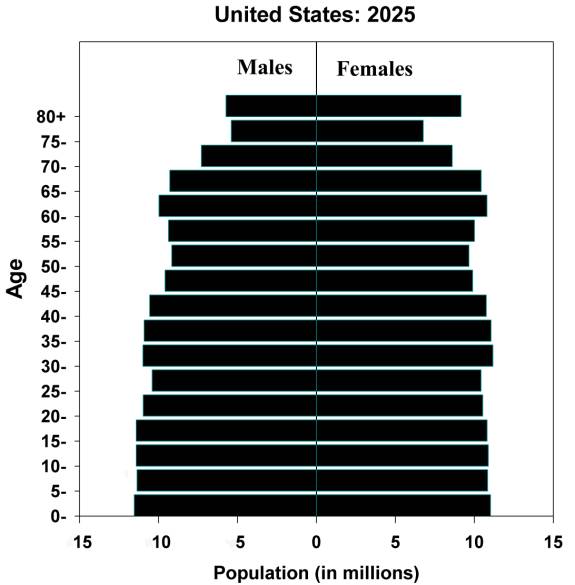

Figures 1-5 About

Here

Demographic

determinants of population aging

To understand the

demographic factors that cause population aging, demographers often

refer to stable

populations (Preston et al. 2001). This population model assumes

that

age-specific fertility and mortality rates remain constant over time,

and this results in a population with an

age distribution that

stabilizes and eventually becomes time invariant as well. Conversely,

this

theoretical model suggests that any change in age structure, and

population

aging in particular, can only be caused by changes in fertility and

mortality

rates. The influence of changes in fertility rates on population aging

is

perhaps less intuitive than that of mortality rates. Everything else

constant,

however, a fertility decline reduces the size of the most recent birth

cohorts

relative to the previous birth cohorts, hence reducing the size of the

youngest

age groups relative to that of the older ones.

The effects of

changes in mortality rates on population aging appear more intuitive,

but are

in fact more ambiguous. If increases in the human life span are

correctly linked to population aging, reductions in mortality rates do

not

necessarily contribute to population aging. More specifically,

mortality

declines among infants, children and persons younger than the

population mean

age tend to lower the population mean age. A moment of thought

suggests

that indeed a reduction of neonatal mortality (i.e., death in the first

month

of life) adds individual at age 0 and should lead to the same partial

alleviation of population aging as an increase in childbearing.

Population aging is thus

related to the demographic transition, that is

the processes that lead a society from a demographic regime

characterized by

high rates of fertility and mortality to another one with lower

fertility and

mortality rates. In the course of this transition, the age structure is

subjected to different influences. In the typical sequence, the

transition

begins with successes in preventing infectious and parasitic diseases

that

benefit infants and young children most. The resulting improvement in

life

expectancy at birth occurs while fertility tends to remain unchanged,

thereby

producing large birth cohorts and an expanding proportion of children

relative

to adults. Other things being equal, this initial decline in mortality

generates a younger population age structure.

After initial and

sometimes very rapid gains in infant and child mortality have been

achieved,

further mortality declines increasingly benefit older ages and are

eventually

accompanied by fertility declines. Both changes contribute to reverse

the early

effect of mortality decline on the age structure, and this synergy is

known as

the double aging process. This corresponds to the experience of

most

developed countries today, but further decomposition suggest that their

history

of declining mortality is the dominant factor in current aging

(Preston, Himes

and Eggers 1989). Mortality declines continue in these countries and

the

decrease in mortality rates among the oldest-old (85+ years) has

actually

accelerated since the 1950s (Gavrilov, Gavrilova, 1991). This latest phase of mortality

decline,

which is concentrated in the older age groups, is becoming an important

determinant of population aging, particularly among women.

The rate of population

aging may also be modulated by migration. Immigration

usually

slows down population aging (in

Dynamics

of population aging

The

current level and pace of population aging vary widely by geographic

region,

and usually within regions as well, but virtually all nations are now

experiencing growth in their numbers of elderly residents (for selected

regions

and countries, see Table 1). The percentage of world population

aged 65

and over only increased from 5.2% in 1950 to 6.9% in 2000. In

Table 1 About

Here

Population aging has the

following notable features:

(1) The most rapid

growth occurs in the oldest age groups – the oldest-old (80+ or 85+

years) and

centenarians (100+ years) in particular. In other words,

population aging

is becoming “deeper” with preferential accumulation of particularly old

and

frail people.

(2) Population aging is

particularly rapid among women, resulting in “feminization” of

population aging

(because of lower mortality rates among women). For example, in

the

(3) Another consequence

of lower female mortality is the fact that almost half of older women

(45%) in

2000 were widows, thus living without spousal support.

(4) Population aging

also causes changes in living arrangements resulting in increasing

number of

older people living alone (about 30% of all non-institutionalized older

persons

in 2000 lived alone in the United States).

(5) Since older persons

have usually lower income and a higher proportion of them are living

below the

poverty line, population aging is associated with poverty, particularly

in

developing countries.

Projections of population aging in the 21st

century

Future population aging will depend on future

demographic trends, but most demographers agree that the fertility and

mortality changes that would be required to reverse population aging in

the

coming decades are very unlikely. According to current population

forecasts,

population aging in the first half of this century should exceed that

of the

second half of the 20th century. For the world as a whole,

the elderly

will grow from 6.9% of the population in 2000 to a projected 19.3% in

2050

(Table 1). In other words, the world average should then be higher than

the

current world record. All regions are expected to see an increase,

although it

should be milder in some regions, such as

If population aging is thus far from limited to

the most developed regions, the countries of these regions will likely

continue

to experience the highest proportions ever known. The forecasts suggest

29.2%

of elderly in the European population as a whole, but more than 30% in

a number

of specific European countries, and perhaps as much as 36.4% in

There is of course some uncertainty with any

forecast, but it is important to note that previous population

forecasts

underestimated rather than overstated the current pace of population

aging. Before the 1980s the process of population aging was

considered as

an exclusive consequence of fertility decline and it was predicted that

the

pace of population aging would decrease after stabilization of

fertility rates

at some low levels. Rapid decline in old-age mortality observed

in

developed countries in the last decades of the 20th century

significantly accelerated population aging. Now the old-age

mortality

trends are becoming the key demographic component in projecting the

size and

composition of the world's future elderly population. Current and

future

uncertainties about changing mortality may produce widely divergent

projections

of the size of tomorrow's elderly population. For example, the

U.S.

Census Bureau's middle-mortality series projection suggests that there

will be

14.3 million people aged 85 and over in the year 2040, while the

low-mortality

(i.e., high life expectancy) series implies 16.8 million.

Alternative

projections, using assumptions of lower death rates and higher life

expectancies,

have produced estimates from 23.5 to 54 million people aged 85 and over

in 2040

in the United States (see Kinsella, Velkoff, 2001).

Social

and economic implications of population aging

While population aging

represents, in one sense, a success story for mankind (massive survival

to old

ages has become possible), it also poses profound challenges to public

institutions that must adapt to a changing age structure.

The first challenge is

associated with dramatic increase in the older retired population

relative to

the shrinking population of working ages, which creates social and

political

pressures on social support systems. In most developed countries,

rapid

population aging places a strong pressure on social security

programs.

For example, the

Population aging is also

a great challenge for the health care systems. As nations age,

the

prevalence of disability, frailty, and chronic diseases (Alzheimer’s

disease,

cancer, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular

diseases,

etc.) is expected to increase dramatically. Some experts raise

concerns

that the mankind may become a “global nursing home” (Eberstadt,

1997).

The aging of the

population is indeed a global phenomenon that requires international

coordination of national and local actions. The United Nations

and other

international organizations developed recommendations intended to

mitigate the

adverse consequences of population aging. These recommendations

include

reorganization of social security systems, changes in labor,

immigration and

family policies, promotion active and healthy life styles, and more

cooperation

between the governments in resolving socioeconomic and political

problems posed

by population aging.

On the positive side,

the health status of older people of a given age is improving over time

now,

because more recent generations have a lower disease load. Older

people

can live vigorous and active lives until a much later age than in the

past and

if they're encouraged to be productive, they can be economic

contributors as

well. Also the possibility should not be excluded that current

intensive

biomedical anti-aging studies may help to extend the healthy and

productive

period of human life in the future (de Grey et al., 2002).

Word Count: 2,793

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Administration

on Aging. 2001. A

Profile of Older Americans: 2001.

De Grey,

Aubrey D. N., Leonid Gavrilov, S. Jay Olshansky, L. Stephen Coles, Richard G. Cutler,

Michael Fossel, and S. Mitchell Harman. 2002. “Antiaging

technology and pseudoscience.” Science,

296: 656-656.

Eberstadt, N. 1997. “World population

implosion?” Public Interest, 129: 3-22.

Gavrilov, Leonid A., and Natalia

S. Gavrilova. 1991. The Biology of Life Span: A

Quantitative Approach. NY, etc.: Harwood Academic Publ..

Kinsella, Kevin, and Victoria A. Velkoff.

2001. An Aging World: 2001.

U. S. Census Bureau, Series P95/01-1,

Lutz,

Wolfgang, Warren Sanderson, and Sergei Scherbow. 2001. “The end of world population growth.” Nature 412: 543-545.

United Nations 2001. World population prospects: the

2000 revision.

Table 1.

Dynamics of Population Aging in the

Modern World

Observed and Forecasted Percentages of the Elderly (65+

years) in

Selected Areas, Regions, and Countries of the World: 1950, 2000 and

2050.

|

Major Area, region and country |

1950 |

2000 |

2050 |

|

World |

5.2% |

6.9% |

19.3% |

|

Africa |

3.2% |

3.3% |

6.9% |

|

|

3.7% |

5.4% |

16.9% |

|

China |

4.5% |

6.9% |

22.7% |

|

India |

3.3% |

5.0% |

14.8% |

|

Japan |

4.9% |

17.2% |

36.4% |

|

Europe |

8.2% |

14.7% |

29.2% |

|

Italy |

8.3% |

18.1% |

35.9% |

|

Germany |

9.7% |

16.4% |

31.0% |

|

Sweden |

10.3% |

17.4% |

30.4% |

|

U.S.A. |

8.3% |

12.3% |

21.1% |

Source:

United Nations 2001.

Figure

1. Youthful

population.

Figure

2. Aged

population.

Figure

3. Intermediate

population.

Figure

4. Projected

extremely old population.

Figure

5. Projected

old population.